We’ve all made our fair share of bad decisions in life. In the best-case scenario, poor decisions lead to suboptimal outcomes that can easily be remediated; in the worst case, poor decisions can incur large costs, including wasted resources and time, and can have lasting undesirable impacts.

So why are poor decisions made, and how can we avoid them? Here are some common decision-making mistakes and how to overcome these obstacles to make better decisions.

Why are bad decisions made?

As humans, we are naturally predisposed to cognitive biases. Our ancestors evolved to make decisions quickly in order to increase chances of survival in the wilderness; after all, assuming that a rustling bush at night is hiding a predator (even if it actually isn’t) is preferable to taking time to study the rustling bush and potentially being killed. Coupled with our social nature and the innate need to fit in with a group, we developed mental shortcuts called heuristics.

While heuristics help us think quickly, they also often cause us to make poor decisions. We’re not very good at evaluating trade-offs involved in our decisions – our perception of the benefits and costs involved is often skewed by emotion or bias, leading to common decision-making mistakes. Although we can’t eliminate biases in our thinking, we can improve our decision-making once we are better aware of them.

Common decision-making biases

To better understand why poor decisions are made, here are some common cognitive biases that lead to poor decision-making. These biases affect us in all types of situations, including poor decision-making in business, government, and our personal lives. We’ve grouped the biases into overarching themes according to which parts of our decision-making they affect.

Risk and loss

Loss aversion

In general, our minds weigh losses more heavily than gains, causing us to prefer to avoid losing something than gaining something of equal value. This tendency is known as loss aversion. For example, if you were to lose $50, the psychological pain would be significantly greater than the joy of winning $50. Loss aversion causes us to make overly cautious decisions and can lead to missed opportunities.

Endowment effect

The endowment effect occurs when people ascribe more value to things merely because they own them. This bias can result in reluctance to part with possessions or investments, even when selling them would be beneficial.

Status quo bias

Status quo bias is the tendency to prefer maintaining things as they are, even though changing them would be more logical or beneficial. For example, even though research suggests that a four-day work week could boost productivity by giving workers more time to recharge, organizations resist making these changes, preferring instead to maintain the status quo.

Sunk cost fallacy

The sunk cost fallacy is the inclination to continue an endeavor once an investment in money, effort or time has been made, even if it’s clear that stopping would be more advantageous. A common example of this bias is staying in an unhappy relationship only because you’ve already invested so much time into it; or continuing an unsuccessful business venture. People often persist with a decision to avoid feeling that their prior investment was wasted, even when it's clear that stopping would be better.

Framing effect

The framing effect happens when the way information is presented influences decisions. For example, if you were choosing between two brands of yogurt where one is labelled “80% fat-free" and the other is labelled “20% fat”, you would be more inclined to choose the first option even though they are equivalent. The framing effect causes people to react differently to the same information depending on whether it's framed positively or negatively, affecting their risk perception and choices.

Probability

Neglect of probability

Neglect of probability refers to our inability to accurately assess the likelihood of an event happening when making decisions. Often, we tend to fixate more on the value of a possible outcome rather than the probability of it occurring: e.g. winning $100 million in a lottery rather than the infinitesimally small chance of having the winning ticket. In other cases, we estimate likelihoods based on anecdotal evidence rather than factual information. These instances of probability neglect can lead to poor risk assessment and unwise choices, such as underestimating the chances of rare but catastrophic events.

Representativeness heuristic

The representativeness heuristic involves judging the likelihood of an event based on how similar it is to something we are familiar with. For example, doctors might diagnose a patient based on how similar that patient’s condition is to a disease’s typical description. While the representativeness heuristic often helps us save time in making reasonable conclusions, it can also create problems, such as discriminating against people based on their similarity to a stereotype, or incorrectly assuming future probabilities based on past events.

Base rate neglect

Base rate neglect is the tendency to ignore general statistical information (base rates) in favor of specific information when making conclusions about the likelihood of an event. This often ties into stereotypes: for example, when asked whether Jamie, who likes to read books (specific information), is more likely to be a librarian or a supermarket worker, many would say a librarian because of the stereotype. However, given that supermarket workers outnumber librarians by about 25:1 (base rate), and that book reading isn't rare, Jamie is probably a supermarket worker.

The base rate neglect happens because we tend to assume general information to be less relevant than specific information. Base rate neglect leads to misjudging probabilities and making decisions based on incomplete or misleading data.

Information processing

Confirmation bias

Confirmation bias causes individuals to seek out and interpret information in a way that confirms their preexisting beliefs or preferences. We often fail to interpret evidence objectively to subconsciously protect our ego. This bias results in selective attention to information that supports desired conclusions, while dismissing or ignoring contradictory evidence.

Anchoring bias

Another bias that inhibits our ability to process information objectively is our tendency to latch on to the first piece of information we encounter – an “anchor” – and deem it as holding more weight than subsequent information. This phenomenon – the anchoring bias – persists even if the initial information was irrelevant. For example, in one famous study, researchers spun a wheel of fortune labelled with numbers 1-100, and then asked participants to guess how many African countries are members of the United Nations. Participants whose wheel landed on a higher number tended to guess a larger number of countries in the UN – even though the two situations are obviously unrelated.

Availability heuristic

The availability heuristic refers to the tendency of our conclusions to be disproportionately influenced by information that is readily available in our memory. For example, after seeing something on the news, we are more prone to overestimating the likelihood of such events happening to us. In particular, events that are recent, vivid or emotionally charged are more easily recalled and can disproportionately influence decisions.

Halo effect

The halo effect is the tendency to let an overall impression of a person, company or product influence specific judgments about them. A common example is that we tend to assume physically attractive people to also be kinder and more intelligent, even if we have no other reason to believe so. The halo effect may lead to one perceived positive or negative trait overshadowing all others in our mind, causing us to fail to evaluate situations objectively.

Judgment

Overconfidence bias

Overconfidence bias is the tendency of individuals to overestimate their abilities, the accuracy of their judgments and their knowledge. Human judgement is highly susceptible to overconfidence: for example, a study found that 73% of American drivers think their driving skills are above average, which is statistically impossible. Overconfidence bias may result in taking on too much risk, making unfounded assumptions, and ultimately poor decisions.

Groupthink

Groupthink occurs when members of a group avoid voicing opposing opinions in order to maintain harmony or keep the peace. This bias discourages creative thinking, leading to a consensus that isn’t thoroughly evaluated. In extreme circumstances, groupthink can lead to the people involved ignoring ethical consequences of a decision, in favor of achieving the group’s goal.

Affinity bias

Affinity bias refers to our tendency to favor people who are similar to ourselves in terms of background, beliefs or interests. We tend to feel more comfortable with people who are like us, and subconsciously reject those that are different from us. This bias can affect decisions in hiring, collaborations and social interactions, often at the expense of diversity and objectivity.

How to make better decisions

We are all susceptible to decision-making biases and mistakes. Symptoms of poor decision-making may include impulsiveness, excessive risk-taking, lack of reflection on one’s knowledge and on the decision-making process and unintended negative outcomes.

Fortunately, however, there are several things you can do to help mitigate those issues. Here are a few best practices to overcome common decision-making mistakes.

Be aware of decision-making problems

The first step to improving decision-making is being aware of common decision-making mistakes and biases and paying attention to where they might affect your decisions. To identify areas that need improvement, you should, in effect, audit your decision-making processes. Fostering a continuous learning mindset also helps you be less susceptible to common decision-making biases that ultimately lead to poor decisions.

Seek feedback from others

Many decision-making mistakes can be prevented by seeking input from other people. Of course, many decisions are naturally made in group contexts, such as in businesses, nonprofits and government organizations.

To avoid groupthink when working with others, having a structured decision-making approach, specialized decision-making tools, and following best practices for group decision-making can help.

Follow a structured decision-making process

To help you avoid making poor decisions, adopt a systematic decision-making approach to incorporate best practices in your decision-making process. Try to include these steps:

- Structure your decision problem

- Think about what the crux of the problem is, and how such a decision should be made.

- Identify different frames; analyze how each frame fits and what it leaves out. Settle on the frame that you and your group find most appropriate.

- Gather knowledge

- Identify criteria that you can use to decide between different options, as well as what your options are.

- Research information relevant to the decision.

- For complex, repeated or high-value decisions, building a model using decision-making software helps to find the relative importance of your criteria in a scientifically valid and reliable manner.

- Analyze your results

- Your methods could include numerical and graphical analyses, sensitivity analysis, and other ways of looking at your data and reaching conclusions.

- Also think about the limitations of your study.

- Collect feedback and reflect on your decision-making process. Use your findings to learn and improve your decision-making process.

Using 1000minds to avoid poor decisions

1000minds software offers a powerful and user-friendly solution for mitigating common decision-making mistakes and facilitating more informed, transparent, and auditable decisions. Here's how the software can address common decision-making pitfalls:

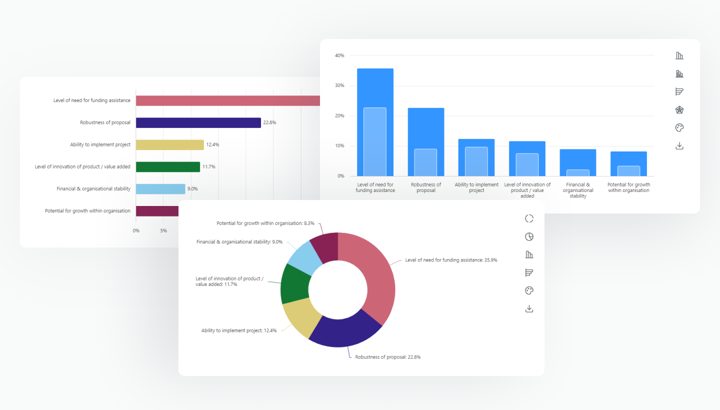

Systematic decision-making method

1000minds provides a structured way to identify the decision problem, weigh criteria and prioritize alternatives, and analyze results. The patented and award-winning PAPRIKA method underlying 1000minds provides scientific validity and transparency to keep your heuristics in check.

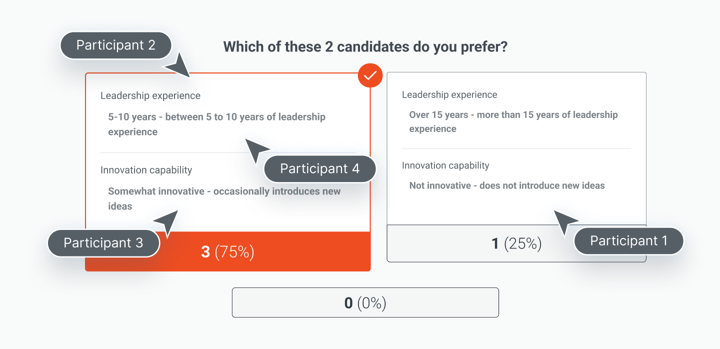

Collaborative decision-making tools

1000minds tools enable users to gather input from multiple decision-makers at every step of the process. A built-in voting feature allows group members to provide their judgements anonymously, followed by discussion of the results in pursuit of consensus. This capability discourages groupthink, while helping individuals understand different perspectives and reach consensus.

Auditable, editable processes

The variety of graphs and charts in 1000minds helps you understand exactly why the alternatives you prioritized were ranked and numerically scored the way they are. 1000minds also facilitates sensitivity analysis, and keeps a record of the way expert judgements were elicited so you can easily review and refine judgements in the face of new information, as well as reflect on the process to improve future decisions.

By leveraging 1000minds software, individuals and organizations can overcome common decision-making mistakes, making more informed, unbiased and accountable decisions that lead to better outcomes. Through its structured approach to decision-making and comprehensive analytical capabilities, 1000minds empowers users to navigate complex decision environments with confidence and clarity.

Share this post on: