Individuals and organizations are faced with making decisions involving trade-offs every day. Unfortunately, we can’t have everything we want all at once – there’s always something that needs to be sacrificed when we make choices.

Understanding what trade-offs entail and how to evaluate them helps us make informed decisions, resulting in optimal allocations of scarce resources at both personal and societal levels.

In this comprehensive guide, we will define what trade-offs are, discuss examples of trade-offs in economics and business, and provide tips for improving your decision-making when trade-offs are involved. We’ll also explore methods for evaluating trade-offs for both small-scale and large-scale decisions.

What are trade-offs?

A trade-off refers to a decision where you must give up, or sacrifice, one thing in order to achieve another. Whenever you cannot have everything at once, a trade-off must be made.

For example, consider choosing what to eat: cooking at home often means cost savings, but it’s more time-consuming. In contrast, ordering take-out saves time, but costs more money.

Making such choices means weighing the benefits and costs of the various options, inevitably requiring trade-offs to be confronted and, ultimately, the best alternative to be identified.

Understanding trade-offs is important because every choice comes with an opportunity cost: what must be given up when you choose one thing over another.

Therefore, it is important to examine everything you’ll have to give up when you choose a particular option – not just the direct costs but also other less obvious indirect costs incurred by not being able to have the next-best alternative as a result of your choice.

For example, if you decide to go to university, your direct cost is your tuition. But if your decision to study means you had to give up a full-time job that you also enjoyed, then, in addition to tuition, your opportunity cost of studying is also the foregone wages you would have earned and enjoyment from your job if you had chosen to work instead.

Examples of trade-offs

Many of the decisions we make every day involve trade-offs. Some examples include increasing physical activity by walking instead of driving, but at the cost of tiring ourselves and taking more time; choosing to work more hours for extra income, but, therefore, having less leisure time; using single-use plastics for convenience, but harming the environment; and so on.

Trade-offs are also inevitable when we decide what products to buy, such as choosing a new laptop from all the models available: we need to make trade-offs between the various models’ screen size and weight, computing power and price, etc. Trade-offs are found in all sorts of applications, including personal decisions, but also business, government, and economics, and more.

What is a trade-off in economics?

Trade-offs are fundamental concepts in economics – the study of how individuals and societies make choices in the face of scarce resources such as natural resources, human talent, money, time, etc. Economics is all about making choices about the best use of scarce resources from the myriad alternative uses possible.

Trade-offs are central to human existence, as encapsulated by these famous quotes from US economist and political commentator Thomas Sowell (2002, 2013):

- “Trade-offs have been with us ever since the late unpleasantness in the Garden of Eden.”

- “There are no solutions, there are only trade-offs; you try to get the best trade-off you can get, that’s all you can hope for.”

Trade-offs in economics are everywhere, including choices made by consumers when purchasing goods and services, decisions made by businesses when investing in new opportunities or making strategic plans, and more.

Governments face trade-offs too: when a government increases spending on something, such as early childhood education, they have to trade-off the other possible things they would have done with the money instead; for example, spending it on defense or healthcare, or paying off government debt or cutting taxes.

“Guns versus butter” and the production-possibilities frontier

A simplified model for representing the trade-offs faced by countries when allocating their scarce resources is the famous “guns versus butter” model, in which it is assumed that a country can produce just two types of goods: “guns”, representing a country’s production of military goods, and “butter”, representing all other (civilian) goods.

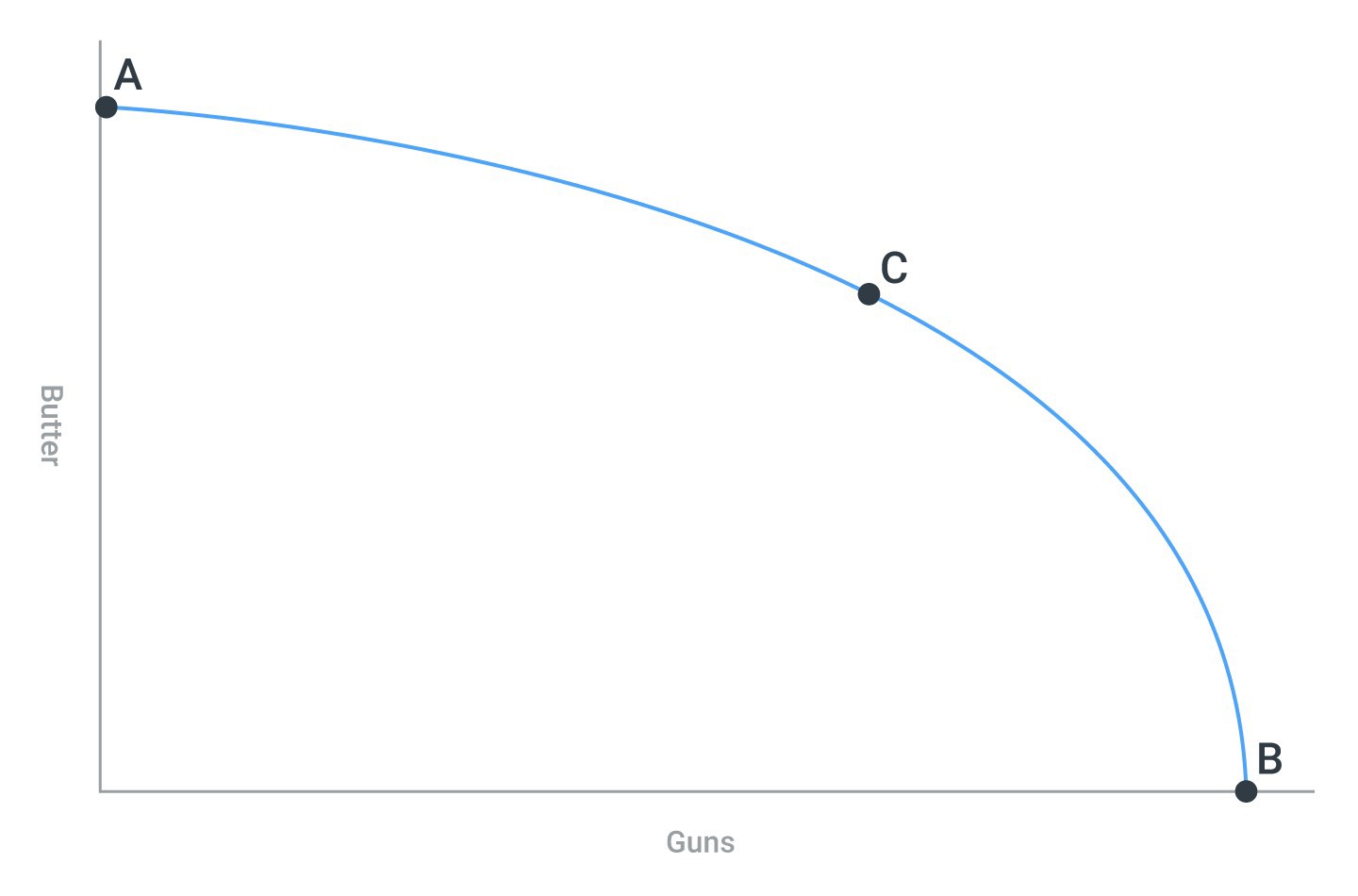

All possible combinations of the maximum quantities of the two goods that can be produced from the country’s available resources are represented by the production-possibilities fronter (PPF), as in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Production-possibilities frontier (PPF) representing trade-offs

Trade-offs between guns and butter are represented by the PPF’s slope, which represents how much butter must be given up – traded-off – to produce one more gun at the various combinations of the two goods (points on the PPF). Notice that the amount of butter that must be traded-off to produce extra guns increases as the country moves away from specializing in butter and towards specializing in guns. This curvature reflects the “law of diminishing returns to production”.

The guns-versus-butter model can easily be reconfigured by changing the goods on the axes to represent analogous pairwise trade-offs in economics faced by countries – e.g. education versus healthcare – and likewise for individuals and organizations.

Trade-offs vs. opportunity costs – what’s the difference?

While a trade-off refers to a decision where one thing must be given up in order to attain another, the opportunity cost refers to the sacrifice that is made. Making choices inevitably requires trading off one thing against another, and every trade-off comes with an opportunity cost: the next-best alternative that is foregone. As the saying goes, You can’t have your cake and eat it too!

For example, when you spend your money on a new phone, the opportunity cost – and what you’ve traded-off – might be buying a plane ticket to go on holiday.

Likewise, in the example of guns vs butter above, the opportunity cost of more “guns” (military spending) is less “butter” (civilian goods), and vice versa.

When making decisions, it is important we also keep in mind the opportunity costs associated with our choices.

What is a trade-off in business?

In business, assessing trade-offs is vital for making strategic decisions or allocating scarce resources. Common strategic trade-offs may include these examples:

- Balancing investment risk versus reward

- Prioritizing projects based on strategic benefit versus monetary cost

- Weighing a job candidate’s level of experience and education versus organizational fit

- Optimizing economic gain versus environmental and social impacts

When making business decisions, it is important not just to consider what benefits you may gain from a decision but also what you may be potentially missing out on, which may have significant effects on profitability.

However, evaluating trade-offs between benefits and costs can be tricky, especially when there are multiple alternatives to choose between and potentially many decision-makers to be involved. Nonetheless, there are some things you can do to help make better decisions when trade-offs are involved.

Consequences of avoiding trade-offs: indecision as a decision

Being faced with difficult trade-offs can be overwhelming, prompting us to put off making any decisions at all for fear of the costs associated with making the wrong choice. However, not making a decision is itself a decision – often with negative consequences.

When struggling with indecision, we may miss opportunities if there is a specific timeframe during which a decision must be made. In other instances, indecision leads to stagnation, and no potential benefits of available options are realized. If you hesitate to invest in professional development or a new business opportunity because you can’t decide which option is best, you might end up missing out on the benefits that any of those choices could have provided.

By failing to choose, we allow circumstances to dictate our outcomes rather than taking control of our future. Often, any well-considered choice is better than no choice at all, as it leads to progress and allows us to learn and adapt from the results of our decision. Therefore, when struggling with difficult trade-offs, remember the cost of inaction and set a deadline for making your decision.

Tips for evaluating trade-offs

Here are four tips to help you evaluate strategic trade-offs more effectively, which can help you make decisions that align with your organization’s best interests and allocate resources more efficiently:

- Ensure that decision-makers are knowledgeable and competent, and include people from diverse backgrounds whose perspectives could uncover valuable information you would otherwise be unaware of.

- Establish explicit limits for how much of a sacrifice you are willing to accept for achieving your goals; for example what reduction in current revenue is acceptable in return for greater future profits?

- Specify explicit criteria and weights representing their relative importance – in effect, quantifying acceptable trade-offs – to be used in support of decision-making.

- Use valid and reliable methods, potentially including specialized software such as 1000minds, to help you assess trade-offs – depending on the application, potentially involving many decision-makers – and keep track of the implications for your decision.

Following these tips can help you evaluate trade-offs properly more effectively, which is crucial for making decisions that align with your organization’s best interests and minimize opportunity costs.

Trade-offs involving multiple factors

Rather than only trading off one thing against another, trade-offs often involve multiple factors that need to be weighed against each other to make a decision.

Consider, for example, if you are a government organization deciding between different options to manage flood risk in low-lying coastal urban areas. Some options may be very effective and moderately scalable, but have unintended environmental consequences; other options may be more environmentally friendly and highly scalable, but not very effective.

Furthermore, there is also the monetary cost involved, potential risk of failure, and time taken to complete the project. Trade-offs such as these, involving multiple criteria, can quickly become very complex and challenging to think about.

There are many approaches to assessing such multi-criteria decision-making problems, with varying degrees of complexity and accuracy. These approaches typically involve weighed-sum models, where the criteria are assigned weights that sum to 1, and the various alternatives of interest are scored based on their performance on the criteria and weights of the criteria. To make this process easier and more accurate, specialized decision-making software is available.

Using 1000minds to simplify decision-making with trade-offs

For decisions that require evaluating complex trade-offs, especially when multiple criteria are involved, using specialized decision-making software such as 1000minds can be very helpful.

1000minds works by asking decision-makers a series of trade-off questions to discover how they feel about the relative importance of the criteria that matter for the decision at hand. Each question involves choosing between two hypothetical, or imaginary, alternatives at a time defined on just two criteria and involving a trade-off.

An example of such a trade-off question appears in Figure 2 – for an application involving prioritizing possible geo-engineering mitigations to climate change such as afforestation, ocean fertilization, etc. based on multiple criteria such as technological readiness and public acceptance.

Figure 2: Example of a 1000minds trade-off question

Such questions are repeated with different pairs of hypothetical alternatives – in the present example, geo-engineering mitigations to climate change – always involving trade-offs between different combinations of the criteria, two at a time.

How decision-makers answer the questions depends on how they feel, based on their expertise and judgement, about the relative importance of the two criteria appearing in each question.

An important advantage of this approach, which is known as the PAPRIKA method, is that such questions are the simplest possible involving trade-offs for decision-makers to think about, and therefore we can have confidence in the accuracy of their answers.

The questions can be answered by a single decision-maker working on their own; or as a group of decision-makers voting on the trade-offs in pursuit of consensus; or by 1000s of participants in a 1000minds survey.

Quantifying trade-offs between criteria

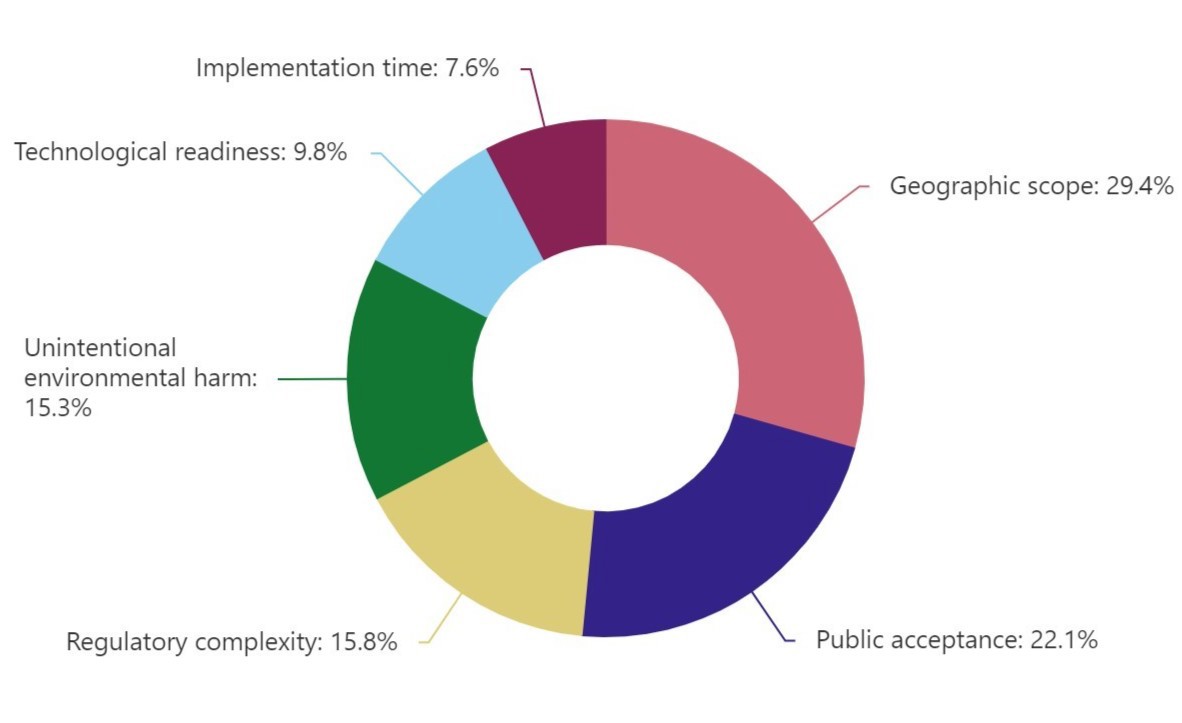

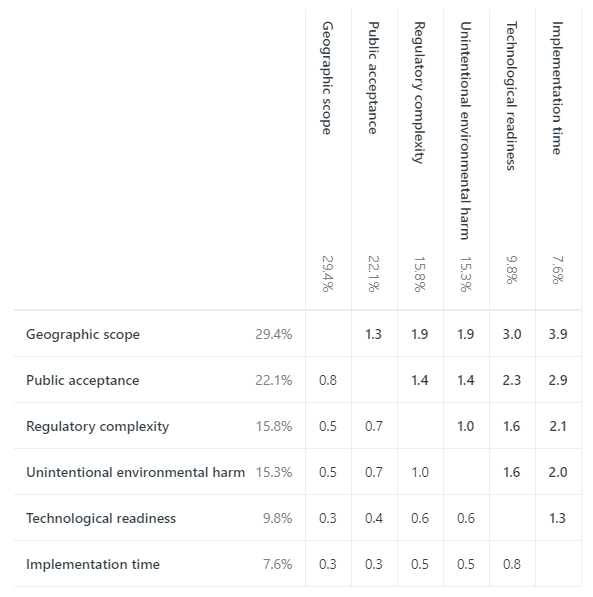

Based on each decision-maker’s answers to the trade-off questions, 1000minds calculates their “preference values” or “utilities”, and scores the alternatives being considered accordingly. These values represent the criteria’s relative importance, or weight – see the donut chart in Figure 3, for six criteria for prioritizing geo-engineering mitigations.

Figure 3: Criteria weights for prioritizing geo-engineering mitigations to climate change

Trade-offs between criteria are often quantified as simple ratios capturing the criteria’s relative importance, as in Table 1 – where each ratio is calculated by dividing the weight on the left by the weight at the top of the table (and notice that corresponding pairs of ratios are inverses of each other).

In some fields, such as Economics, these ratios are known as “marginal rates of substitution” (MRS).

Table 1: Relative importance of criteria

Value-for-money chart and efficiency frontier

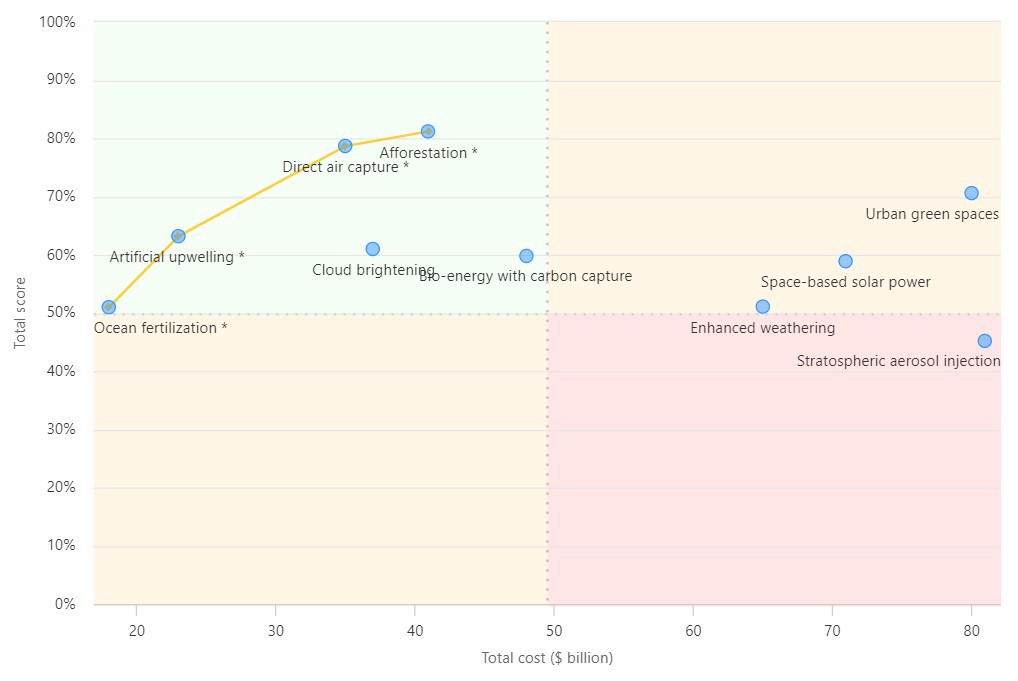

For the alternatives being considered, their total scores – i.e. a weighted-sum of their performance on the criteria, interpretable as representing their benefits – can be compared against their costs in a value-for-money chart, as in Figure 4.

In the chart, the alternatives (i.e. geo-engineering mitigations) in the top-left quadrant represent the best value-for-money, or biggest “bang for buck”.

The golden line in the chart is the efficiency frontier, also known as the “Pareto frontier”, which identifies the alternatives that “dominate” all others with respect to the variables on the chart’s two axes.

To say that one alternative (geo-engineering mitigation) “dominates” another means that the first alternative has a higher total score (benefit) and a lower cost than the dominated alternative; and, thus, it is unambiguously better.

However, when it comes to comparing alternatives on the efficiency frontier, the comparison depends on possible trade-offs between the two axes that are acceptable to the decision-maker.

A higher cost can be compensated for, to some degree, by a higher total score (benefit), and vice versa – but at what “rate of exchange” between the two axes? The answer depends on how the decision-maker feels about the trade-off between the alternatives’ total scores and costs.

1000minds decision-making tools enable you to better assess trade-offs and opportunity costs by making them more explicit and transparent – resulting in decisions you can trust and, if need be, defend.

Figure 4: Value-for-money chart and efficiency frontier

Conclusion

In every decision we make, there are always trade-offs to be faced. Understanding what such trade-offs and their associated opportunity costs entail and how to manage them is essential. Following processes for evaluating trade-offs, including using specialized tools like 1000minds, can help organizations improve decision-making. Try a free 15-day-trial today, or book a free demo to see how 1000minds can help your organization make better decisions.

References

T Sowell (2002), A Conflict of Visions: Ideological Origins of Political Struggles, Basic Books.

T Sowell (2013), Ever Wonder Why? And Other Controversial Essays, Hoover Press.

Share this post on: